Henry Chronowski

Portfolio

Project maintained by henrychronowski Hosted on GitHub Pages — Theme by mattgraham

Planetary Planter’s Dynamic Sky

The Problem

While developing Planetary Planter we had an issue: The simple starry night texture (below) that we had been using as our skybox throughout testing was no longer cutting it. Why? Well, for one we had a sun in the sky and having a black starry night with a bright, Earth-like sun among a dark starry sky was creating some cognitive dissonance in testing sessions. Additionally, one of the core tenets of the game is having the player as immersed in the world as is possible, and this static image was not doing that at all, as well as that we now had several different biomes in the game that we wanted to all be exactly as immersive but feel vastly different.

As such I was tasked with creating a system with the following criteria:

- It needs to be non-static. We want the environment to feel a live, the sky should be fluid and convey life, not a painted background

- It needs to have states. We want the different biomes to feel different, having saved states will allow this

- It needs to be configurable. Designers need to be able to customize this for different biomes so it should be easy and intuitive to modify in-editor

- It needs to work with the HDRP. We are using Unity’s HDRP in order to gain the visual fidelity that comes with it, it needs to work with it and especially global illumination

Initial Attempts

My first gut instinct was to reach for the low hanging fruit and just using a simple shader to give the static texture a bit of motion. This turned out to be significantly more difficult than initially anticipated, because as I eventually found out after trawling through many levels of HDRP documentation it is nowhere near as simple as that. For the HDRP you can not just have a single texture with a single shader, as the only texture-based option for a skybox is an HDRI cubemap. While on paper you can write a custom shader for it based off of the Unity one, several days and sleepless nights spent going between struggling to understand and modify the monolithic shader code and being confused while following documentation only to learn it had been deprecated with no updated replacement showed it to be a futile effort in the time I had available to me. The other options were either a static gradient or a fully procedural sky. Static wouldn’t work for my purposes so procedural it was!

Unfortunately, turns out writing a custom procedural sky in the HDRP also wouldn’t work. The procedural sky was deprecated in Unity 2019.3 (this was a very common theme throughout this project) and replaced by the Physically Based Sky, which while the tech behind it is very cool did not do what we needed it to. Besides documentation issues stemming from rapid undocumented updates meaning that their tutorials on how to set it up were inaccurate, the Physically Based Sky was really only capable of simulating, well, a physically based sky, which was not incredibly helpful for the stylized art that we were utilizing. Additionally, and most importantly, due to the intense math involved in Rayleigh and Mei scattering the calculations only run once and are simply stored for use during runtime, which means that we would not be able to easily change the sky between parts of the level where the biomes were different.

This, combined with complications with our curved world that I will go into in another blog post, caused us to make the difficult decision to actually switch off of the HDRP. Even though that visual fidelity was incredibly important for the immersive nature of the game, it was simply causing too many workflow and implementation problems for us to keep going with it. Even though it was essential for us that the game looked as graphically good as was possible, if we can’t get the things that are supposed to look good working because of the HDRP there was no point in using it. The core feature we minimally needed was some form of global illumination, which after more research I figured out how to get working in the standard URP decently well, so it was off to the URP. Luckily this made everything significantly easier, as in the URP as in the old Built-in Render Pipeline I could simply just create a skybox material and edit it. I stuck with the procedural angle though, since this would make it significantly easier to alter the skybox between biomes.

Now as any good programmer would do I started out my new implementation in the URP by first researching to see if anyone had done anything similar, and unsurprisingly they had! Jannik Boysen has written this very helpful blog post that I worked off of for the main shader that I used. The base result of their shader is a good way along what we wanted:

I found their blog post very helpful as it does a good job of explaining the why and how while giving a simple example implementation. I initially simply worked through the blog, adding my own visual customizations to match the visual style of Planetary Planter. Given our space setting I wanted to make our sky more evocative of those pictures of the Milky Way during the night, where you can see not only the distinct stars but the clouds of gas and nebulae in addition to giving our sun more detail and configurability. If you would like to view my exact work in Shadergraph feel free to view the project on GitHub. With this initial step done with the help of Jannik’s blog we have the first requirement done, but we still need to make it state-based and configurable by designers.

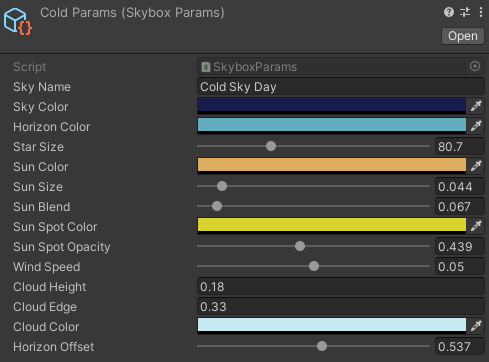

Luckily this was significantly easier than the massive journey to write a skybox shader. In order to make a state-based system that the designers can edit in Unity my brain immediately goes to Scriptable Objects, which allow the designers to make effectively data objects with the normal create menu that they are used to. Additionally, we can easily store these scriptable objects in a manager class allowing us to use and manipulate them at runtime. Since I know we’re going to be visually transitioning between skybox settings at some point this also gives us the ability to put that transition logic within the actual data storage object, simplifying and compartmentalizing.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

[System.Serializable]

[CreateAssetMenu(fileName = "Skybox Parameters", menuName = "Skybox/Skybox Parameters", order =1)]

public class SkyboxParams : ScriptableObject

{

public string SkyName;

public Color SkyColor;

public Color HorizonColor;

[Range(50f, 150f)]

public float StarSize = 100f;

public Color SunColor;

[Range(0f, 0.5f)]

public float SunSize = 0.1f;

[Range(0f,1f)]

public float SunBlend = 0.2f;

public Color SunSpotColor;

[Range(0f, 1f)]

public float SunSpotOpacity = 0.5f;

[Range(0f, 0.1f)]

public float WindSpeed = 0.05f;

public float CloudHeight;

public float CloudEdge;

public Color CloudColor;

[Range(0f, 1f)]

public float HorizonOffset = 0f;

// Lerps between two SkyboxParams given an interp factor

static public SkyboxParams Lerp(SkyboxParams from, SkyboxParams to, float interp)

{

SkyboxParams result = SkyboxParams.CreateInstance<SkyboxParams>();

result.SkyColor = Color.Lerp(from.SkyColor, to.SkyColor, interp);

result.HorizonColor = Color.Lerp(from.HorizonColor, to.HorizonColor, interp);

result.StarSize = Mathf.Lerp(from.StarSize, to.StarSize, interp);

result.SunColor = Color.Lerp(from.SunColor, to.SunColor, interp);

result.SunSize = Mathf.Lerp(from.SunSize, to.SunSize, interp);

result.SunBlend = Mathf.Lerp(from.SunBlend, to.SunBlend, interp);

result.SunSpotColor = Color.Lerp(from.SunSpotColor, to.SunSpotColor, interp);

result.SunSpotOpacity = Mathf.Lerp(from.SunSpotOpacity, to.SunSpotOpacity, interp);

result.WindSpeed = Mathf.Lerp(from.WindSpeed, to.WindSpeed, interp);

result.CloudHeight = Mathf.Lerp(from.CloudHeight, to.CloudHeight, interp);

result.CloudEdge = Mathf.Lerp(from.CloudEdge, to.CloudEdge, interp);

result.CloudColor = Color.Lerp(from.CloudColor, to.CloudColor, interp);

result.HorizonOffset = Mathf.Lerp(from.HorizonOffset, to.HorizonOffset, interp);

return result;

}

}

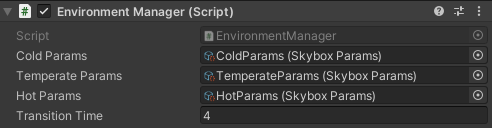

The next step was to create a manager that has the ability to store several skybox parameters, associate them with different biomes, and then transition between them. For this I utilized a singleton for the dual purposes of ensuring that the manager is unique within the scene and also so that other systems can more easily trigger a skybox change, giving designers more choices and options. For instance, if we wanted to have an event in the world where the sky went black or the sun suddenly went out that could be scripted utilizing this manager. Since I knew we were only planning to have 3 biomes for release, I just hardcoded in slots for skybox parameters for those 3 separate biomes, storing them in an array using an integer enum for the index, allowing easy immediate access to each one.

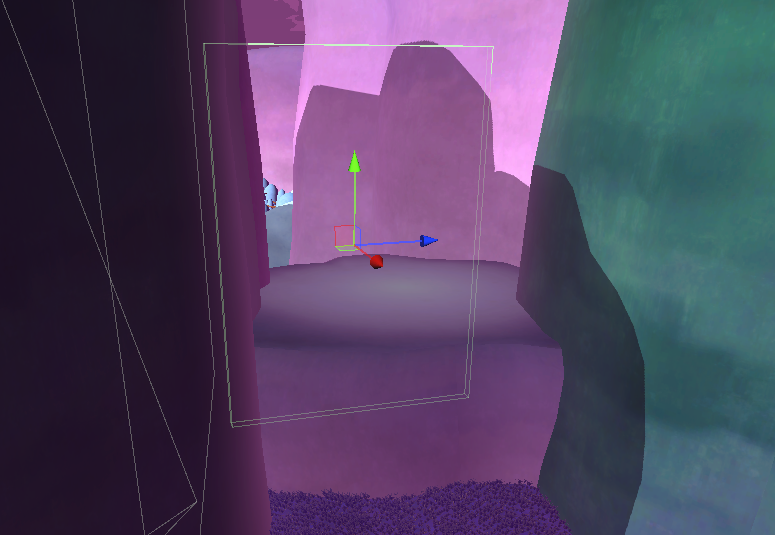

I did not want to have the manager itself trigger transitions with a variety of colliders as first there could be many different spots where a transition is necessary, and second because it would then be difficult to easily tell what biomes we were switching between without doing a bunch of hacky logic or other external methods. In order to trigger skybox transitions I created a third class which simply contained a collider, the knowledge of what biome it transitioned into, and the logic to tell the environment manager to transition to the correct biome when triggered. These were then placed at each transition section between the biomes, making it so that when the player entered the path to the new biome the sky would be the correct vibe by the time they were fully inside.

The workflow was now built for designers to create settings for a biome using the common Unity asset creation workflow, save them, assign that asset to the biome in the environment manager, and have it automatically transition between them as the player moved through the game. That ticks off all of the remaining requirements that we initially listed! This is the system that is still implemented in the released game today.

There was only one further issue that cropped up, which because of the programming patterns followed was easily solved. After a bit more development and testing it became apparent that we needed a fast-travel system so that the player could more quickly and easily get from biome to biome in the later game. This presented the issue that when fast-traveling the player did not pass through the placed transition volumes to trigger the sky changing, setting the logic flow off and offsetting the skybox settings by a biome for the rest of their play session. Luckily, since I had already designed the manager as a singleton with the actual trigger functionality broken out into separate objects, this enabled the programmer working on the fast travel system to simply add the same logic that was used in the transition volumes to their fast travel points, triggering a skybox transition and maintaining the immersion that we were looking to keep.

Important Points

These points are just some takeaways I have from the project, not necessarily connected to each other but all important.

The majority of the difficulty in this process was really in dealing with Unity’s HDRP in the first place, and the main lesson that I have taken away from that is that it is absolutely essential to actually research before making a decision as impactful as choosing the rendering pipeline for your game. Not to say that we did no research into that decision, but we were focused significantly more on the capability for graphical fidelity than whether or not we would actually be able to benefit from it. Trying to find ways to shoehorn our very specific stylized art into the HDRP’s photorealistic tendencies took up many valuable hours that could have gone towards a myriad of other things. If we had stepped back from the excitement of having the best possible graphics and instead thought more of what graphics were necessary for our vision this would have been a much easier process starting out.

I placed such a great importance on ease of use in this system for a variety of reasons. The environment manager didn’t need to be as robust and compartmentalized as it is in order for it to function, but that compartmentalization of functionality and data made dealing with new situations like the fast traveling easier down the road and also helped to minimize the chance of accidents breaking systems. I have found that in my system design I like to think of the team like a program; if there is no real need to know the private variables of a class from another class, it is always better to limit access to avoid undefined behavior. Sure, many designers would be perfectly capable of going in and adding a function to do the exact type of transition that they want from the exact biome that they want, but having a system where there are predefined interfaces, data containers, and functions that external users and classes interact with minimizes the chances of accidentally breaking something, allows for easy modification of the underlying logic, and ensures that everything working with that system is doing it in the same way.